Introduction to ASP.NET Core

Before we can get started, we need to look at what ASP.NET actually is.

What is ASP.NET Core?

ASP.NET Core is a framework for building websites in C#.

That's a little underwhelming, but there are some important nuggets buried in that simple statement.

Firstly, ASP.NET gives you all the tools you need to build the website - as long as you don't have unusual needs for your website, you can build your website just with the tools that ASP.NET provides.

Secondly, ASP.NET websites are just C# programs. They work a lot like a terminal program (in fact, in this series we will treat the programs we write like regular terminal programs and use dotnet run to execute them). If you have experience building website backends in Python or Javascript, this will feel familiar. However, if you're coming from PHP, this is going to feel weird for awhile. PHP websites are collections of script files that get executed on demand, but websites in other languages like C# are computer programs that constantly run. In PHP, each time a page is requested, it has a blank slate - any in-memory data from previous requests is completely lost. But in C# and other languages where your website is a computer program, much of the in-memory data is persistent across requests.

Scaffolded files

Now that we know what ASP.NET is and what we need to do to complete the project, let's take a closer look at the code that dotnet generated for us.

appsettings.json

First glance at appsettings.json - this is a configuration file that contains settings related to your application.

{

"Logging": {

"LogLevel": {

"Default": "Information",

"Microsoft": "Warning",

"Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime": "Information"

}

},

"AllowedHosts": "*"

}The Logging key contains configuration for ASP.NET's built-in logging functionality. Most often you'll use a more comprehensive logging solution like Serilog, but when you're first starting out, the built-in logging is fine.

The AllowedHosts key lets you select which hosts are allowed to access your site, based on the value of the Host HTTP Request Header. Since we will be using Nginx as a reverse proxy, we will leave this as * (which allows all hosts) and if you need to restrict host access, Nginx can handle that.

Program.cs

If you open Program.cs, you will see it looks mostly like a standard Program.cs file with a Main method.

// Program.cs

// Excluded using statements

namespace header_parser

{

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

CreateHostBuilder(args).Build().Run();

}

public static IHostBuilder CreateHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(webBuilder =>

{

webBuilder.UseStartup<Startup>();

});

}

}The Main method only does one thing: starts the ASP.NET website. It does this by calling CreateHostBuilder(), which you can see is also defined in Program.cs, followed by Build() and Run(). You won't have to do anything with CreateHostBuilder until you've been working with ASP.NET for awhile, so we'll take it for granted here. Just notice that CreateHostBuilder has the line webBuilder.UseStartup<Startup>();, which is how the Startup.cs file is linked to the application startup process. Beyond that, you can get through the entire FCC Microservices Certification without knowing anything about Program.cs.

Startup.cs

This is where the interesting stuff is happening.

namespace header_parser

{

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to add services to the container.

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddControllers();

}

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints => { endpoints.MapControllers(); });

}

}

}Breaking down Startup.cs

There's a lot going on here, so let's start at the beginning.

Startup.StartupThe constructor receives anIConfiguration, which is an object containing your configuration fromappsettings.json. It also contains some useful helper methods for getting certain standardappsettings.jsonvalues - for example, database connections are stored in theConnectionStringsobject key inappsettings.json, soIConfigurationcontains a definition forGetConnectionStringto retrieve these. (We will go over this later in greater detail - for now, we won't be usingIConfiguration.)Startup.ConfigureServicesThis method receives anIServiceCollection, which is an object that interacts with ASP.NET's dependency injection framework. Dependency injection is built right into ASP.NET, and you'll use it frequently. If you don't know what dependency injection is, you can read about it in this great article from FreeCodeCamp.Startup.ConfigureThis method receives anIApplicationBuilder, which is an object that defines the behavior of the application, and anIWebHostEnvironment, which is an object containing information about the current environment. This is the place where our first application is going to do all its work.

Let's look at these last two methods, line-by-line.

Startup.ConfigureServices

Here's the code:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddControllers();

}This one is pretty simple. All it does by default is add controllers to the dependency injection container (remember the Controllers directory we deleted last lesson? that was what this does). Controllers contain the endpoints of your API and its behavior, but we won't be using them for awhile. The first couple projects in the FreeCodeCamp Microservices Certification are simple enough that controllers are overkill.

Startup.Configure

Here's the code:

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints => { endpoints.MapControllers(); });

}There's a lot more going on here, so we'll look at this method line by line.

if (env.IsDevelopment()) ...This checks to see if the application is in development mode or production mode. There are a couple different ways of setting environment variables in your ASP.NET application, and we'll look at these later - but for now, just know that ASP.NET uses theASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENTenvironment variable to determine what mode it should be in. If this variable isn't set, it defaults toProduction, so be sure to set it when you're developing your application!app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage()This tells the application to use the developer exception page if the application is in development mode. The developer exception page prints all sorts of useful information when an unhandled exception occurs, like the HTTP headers and the .NET stack trace.app.UseHttpsRedirection()This tells the application to force users to redirect to the secure version of your website (HTTPS). This only works if you have an SSL certificate configured.app.UseRouting()This enables the application to use endpoint routing, which will be required for almost all API applications. By itself,app.UseRouting()doesn't do anything useful - it must be followed byapp.UseEndpoints(), which we'll cover in a moment.app.UseAuthorization()This adds authorization capabilities to the application. By itself, it just enables authorization but doesn't do any authorization configuration - that's done inStartup.ConfigureServices, but it's beyond the scope of this series.app.UseEndpoints(...)This tells the application how to map requests to the app. There are a number of ways to configure endpoints, and we will be covering some of these in a later lesson.... endpoints.MapControllers() ...This tells the application to map the controllers (remember theControllersdirectory) to endpoints. We will be covering this in more detail in a later lesson.

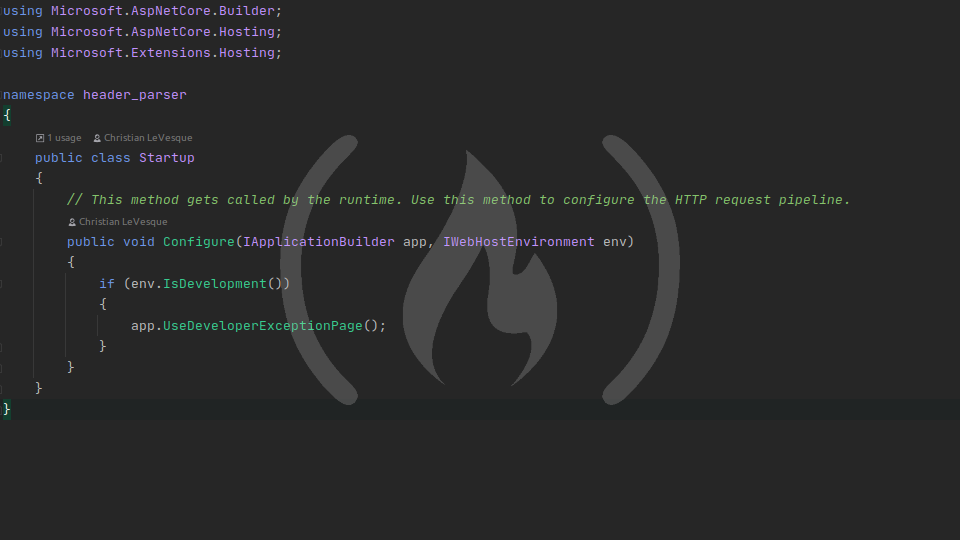

Cleaning up Startup.cs

Now that we have a better idea of what's going on here, we're going to empty most of the file. Most of this code supports a larger application, and our microservice just doesn't need all the cruft.

- Delete the

Startupconstructor and theConfigurationproperty, because we won't be accessing theConfigurationin this app - Delete the

ConfigureServicesmethod, because we don't have controllers and that's the only service currently getting configured - Delete the call to

app.UseHttpsRedirection(), because we don't need HTTPS redirection (when using Nginx as a reverse proxy, it's better to let Nginx handle HTTPS and just use HTTP for your app) - Delete the call to

app.UseRouting(), because this app is simple enough that it doesn't need endpoint-based routing - Delete the call to

app.UseAuthorization(), because we don't need authorization services in this app (authorization services are beyond the scope of this series) - Delete the call to

app.UseEndpoints(), because we deletedapp.UseRouting()andapp.UseEndpoints()does nothing withoutapp.UseRouting()(actually, if you try to run your app withapp.UseEndpoints()and withoutapp.UseRouting(), your app will throw an exception). - The

dotnetCLI also scaffolds a bunch ofusingstatements into your app - many of thoseusingstatements are needed in medium-to-large applications. If you're using a full IDE like Visual Studio or Jetbrains Rider, you probably notice that you only need three of theseusings, so go ahead and delete all of them exceptMicrosoft.AspNetCore.Builder,Microsoft.AspNetCore.Hosting, andMicrosoft.Extensions.Hosting.Microsoft.AspNetCore.BuilderprovidesIApplicationBuilderandIApplicationBuilder.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();Microsoft.AspNetCore.HostingprovidesIWebHostEnvironment; andMicrosoft.Extensions.HostingprovidesIWebHostEnvironment.IsDevelopment(), which is an extension method.

Your Startup.cs file should now look like this:

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Builder;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Hosting;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Hosting;

namespace header_parser

{

public class Startup

{

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

}

}

}Configuring the application port

Your ASP.NET application runs like a computer program, but it listens over HTTP (since it's a website, after all) so it needs to run on a specific port. By default, your application is going to run on http://localhost:5000 and https://localhost:5001, but we don't need HTTPS support for our app (and if we do, we'll use Nginx to supply that) so let's set the app just to run on port 5000. To do that, add "Urls": "http://127.0.0.1:5000" to the appsettings.json configuration file. Your appsettings.json should now look like this:

{

"Logging": {

"LogLevel": {

"Default": "Information",

"Microsoft": "Warning",

"Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime": "Information"

}

},

"AllowedHosts": "*",

"Urls": "http://127.0.0.1:5000"

}That's it!

Now run your project in the terminal with dotnet run just to make sure everything works properly. You should see something about like this in your terminal (this will vary slightly depending on what operating system you use for development):

/usr/share/dotnet/dotnet /home/christian/code/fcc/header-parser/bin/Debug/netcoreapp3.1/header-parser.dll

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Now listening on: http://127.0.0.1:5000

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Application started. Press Ctrl+C to shut down.

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Hosting environment: Production

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Content root path: /home/christian/code/fcc/header-parserYou're ready to start writing code!